High-Speed Machining Means More Than Quick Spindles

Data collection, networking and machine design options are driving notable improvements and cost savings.

Where high-speed machining is concerned, the fastest-spinning spindles or precision axis adjustments down to the micron are useless if your job crashes. As Jim King, president and COO, Okuma America Corp. (okuma.com), put it, “An ‘oops’ on a quarter-million-dollar titanium engine casing three-quarters of the way through machining is a heart attack waiting to happen.”

Speaking at a late-2018 panel discussion, King said strategies for taking time out of the cut and insuring performance all the way through machining cycles are increasingly dependent on the machining center’s ability to collect and process the data necessary for making real-time adjustments throughout part production. From synchronizing tool-changer servos that make tool changes quicker as doors open and close to eliminating pauses in relay signals, no job is too small for improvement, and time savings no matter how minute quickly add up.

First, Connect

A data-connection strategy need not be complicated, King says. Open-source standards like MTConnect (mtconnect.org) provide strategies for connecting machining centers and production equipment from numerous builders and make shop data available in XML with data item definitions that don’t vary by manufacturer. Data collection, while becoming more straightforward, can quickly become overwhelming and experts advise to keep it simple in the beginning. Identify and prioritize use cases like machine-tool monitoring, job scheduling, or lights-out manufacturing, then identify how your machines can output data. Evaluating and working with your facility’s IT and network infrastructure, you can start connecting machines yourself or find software integrator and engineering partners.

When the machine tool is also a data collector, it becomes relatively easy to start identifying important parameters to monitor, such as spindle bearings, vibration, tool temperature, and heat and humidity inside the work envelope, to name but a few. “All this allows the machinist to optimize his machine over the long haul and operate much more predictively,” King said. “You can start making better operational decisions based on individual machine and job data.” Unplanned downtime shrinks as a result.

Then Network

M-1 Tool Works, located in McHenry, IL, northwest of Chicago, was started by race car driver Martin Ryba in 1984 to produce racing parts and components. The shop built a reputation for high-quality, high-precision parts built on multi-axis milling and turning equipment but was not set up to be a high-volume production operation. “We’re now at 50 machines with about 40 employees located in two buildings, but I would say 80 percent of our business consists of orders for 10 parts or less,” says Rusty Thielsen, M-1 project manager.

With 14 seats of CAD-CAM software, M-1 machinists program their own parts at their own machines. What was desired was the capability to send programs to any machine in M-1’s two buildings. “At a time when programs were getting larger and more complex, this meant downloading programs onto flash drives and hand-delivering them to the machines available to work on them,” Thielsen explains.

Searching to improve, M-1 became aware of Cimco, a CNC communication and networking software supplier with world headquarters in Copenhagen and Midwest headquarters in Elgin, IL. Providing CNC editors, manufacturing data collection, and manufacturing data management software, Cimco also provides DNC MAX networking software, which M-1 installed through local Cimco distributor Shopware Inc.

“M-1 was in the sweet spot for benefitting from a DNC (distributed numerical control) software system,” says Ryan Mermall, senior applications engineer and service coordinator at Shopware. “The ideal target would be any customer with CNC machines that needs to find a solution on how to transfer programs to the machine while having a system to back up and organize them. Cimco supports customers that have 1 - 4,000 machines.”

Typically, customers can automate the way programs are getting transferred to CNC equipment, Mermall explains. In addition, users get tighter control of program revisions and user permissions on who can do what with the main program in the software. Other robust features include dynamic federate and spindle speed adjustment, parameter offsets, and advanced logging and backup/versioning.

“Now our programmers can write programs and get them to any machine in both our buildings and manage them from a central server,” Thielsen says. “Programs are into the machines faster and the programs themselves are much more reliable. It makes us a better shop and much more efficient.”

Every time M-1 adds new equipment, the company adds it to their Cimco network. Cimco supports numerous controls including FANUC, Haas, Mazak, Fagor, and more. Combined with RS-232 communications hardware (“Moxa boxes”) M-1 has hooked up its legacy equipment to Cimco as well. “We are managing larger and more complex programs much faster and more efficiently,” Thielsen says. Any program changes or adjustments sent back to DNC-NAX can be automatically raised in a version or stored in a quarantine area. This keeps a much tighter lid on tracking changes or reverting to previous versions if necessary. “Our internal non-conformance is much lower as a result,” he adds.

Added Functions

Machine design and controls expertise also can speed production and save significant time and expense on selected jobs by adding functionality and eliminating the need for additional capital equipment. Turn-Cut is a programming option available on Okuma horizontal machining centers that allows the machine to create bores and diameters that include circular and/or angular features. Allowing users to turn features on large, unbalanced parts on the same platform where standard horizontal CNC machining functions also take place, eliminates the need for special-purpose machines, tooling, fixtures or add-on components. Valves, pipes, and manifolds are ideal candidates.

It works by synchronizing the X and Y circular motion with the machining center’s spindle angle to ensure the tool edge maintains its programmed path at all times. Turn-Cut is turned on by a G-code in the program and follows standard lathe programming conventions to describe the desired path.

In addition, since it is a programming option, Turn-Cut enhances the use of the horizontal machining center without adding special attachments or additional motors or servos, where the added weight might restrict its use during normal CNC machining.

RELATED CONTENT

-

When Automated Production Turning is the Low-Cost Option

For the right parts, or families of parts, an automated CNC turning cell is simply the least expensive way to produce high-quality parts. Here’s why.

-

On Electric Pickups, Flying Taxis, and Auto Industry Transformation

Ford goes for vertical integration, DENSO and Honeywell take to the skies, how suppliers feel about their customers, how vehicle customers feel about shopping, and insights from a software exec

-

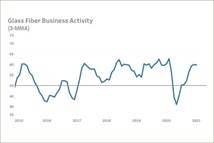

Plastics: The Tortoise and the Hare

Plastic may not be in the news as much as some automotive materials these days, but its gram-by-gram assimilation could accelerate dramatically.