Self-Driving Cars' Age-Old Question

While autonomous tech is touted as a potential safety panacea that will enable greater mobility for the elderly, it initially could have the opposite effect.

The transition toward self-driving cars is on a collision course with a growing demographic group: elderly drivers.

The number of people living in the U.S. who have surpassed their 70th birthday is forecast to jump from 34 million in 2017 to 53 million in 2020. Many already can be viewed in your rearview mirror or racing ahead on the highway.

Indeed. More than 80% of the septuagenarian-plus crowd have a driver’s license. And those who do are logging more miles. Government data show the average annual mileage traveled for such drivers grew by 65% from 1995 to 2017, compared with 37% for those who were age 33-54 during the period.

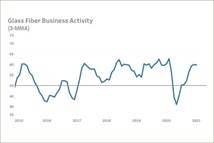

Skill Assessment

Driving skills tend to improve with age. Up to a point. The age of diminishing abilities (reflected by accident rates and insurance claims) is about 70, according to the Insurance Institute of Highway Safety (IIHS).

Source: IIHS

It’s not brain surgery, but it is science. “Physical, cognitive and visual abilities may decline with advancing age for some people,” IIHS notes. Such functional impairments can interfere with driving, especially in stressful or challenging driving situations such as turning left, merging or changing lanes.

Unsafe at Any Age?

Here’s where autonomous tech comes in. One of the main benefits of these systems is improved safety, including under operating conditions in which seniors struggle. Problem solved?

Nope. Let’s forget about fully self-driving (Level 4/5) cars, which aren’t likely on a large scale anytime soon. But semi-autonomous (Level 2/3) models are starting to hit the road. They require drivers to stay alert when the vehicle is under its own operation and quickly take control as necessary. These types of handoffs—a concern with any driver—can be particularly challenging for the elderly.

Source: Newcastle University

A recent study conducted by Newcastle University in the U.K. underscores the problem. Participants were tested on a driving simulator to measure how quickly and adeptly they were able to switch from autonomous to manual operation.

It took younger drivers (20-35) a full seven seconds to go from being totally disengaged—turned away from the steering wheel and reading from an iPad—to assume control and navigate around an obstacle.

Those aged 60-81 required 8.3 seconds, which equates to an additional 115 ft when traveling at 60 mph. Older drivers also had less smooth transitions, which resulted in erratic control of the steering wheel, accelerator and brakes. When driving in urban scenarios, the group recorded two-thirds more collisions and critical encounters than their younger counterparts. All this was under clear conditions with a control group described as “active.” The results were worse across the board during rain, snow and fog.

Help Needed

Some participants found the whole process disconcerting. One 77 year-old laments that it felt “very strange to be a passenger one minute and the driver the next.”

Part of the problem is that new technologies tend to be developed by relatively young engineers, without much input from their elders. While not much can be done to speed a person’s reaction time, improvements can be made on how people interact with systems and making users more comfortable with automated features.

One suggestion from Newcastle participants: Provide periodic updates to keep occupants abreast of trip details, similar to GPS guidance reminders.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Multiple Choices for Light, High-Performance Chassis

How carbon fiber is utilized is as different as the vehicles on which it is used. From full carbon tubs to partial panels to welded steel tube sandwich structures, the only limitation is imagination.

-

GM Develops a New Electrical Platform

GM engineers create a better electrical architecture that can handle the ever-increasing needs of vehicle systems

-

Things to Know About Cam Grinding

By James Gaffney, Product Engineer, Precision Grinding and Patrick D. Redington, Manager, Precision Grinding Business Unit, Norton Company (Worcester, MA)